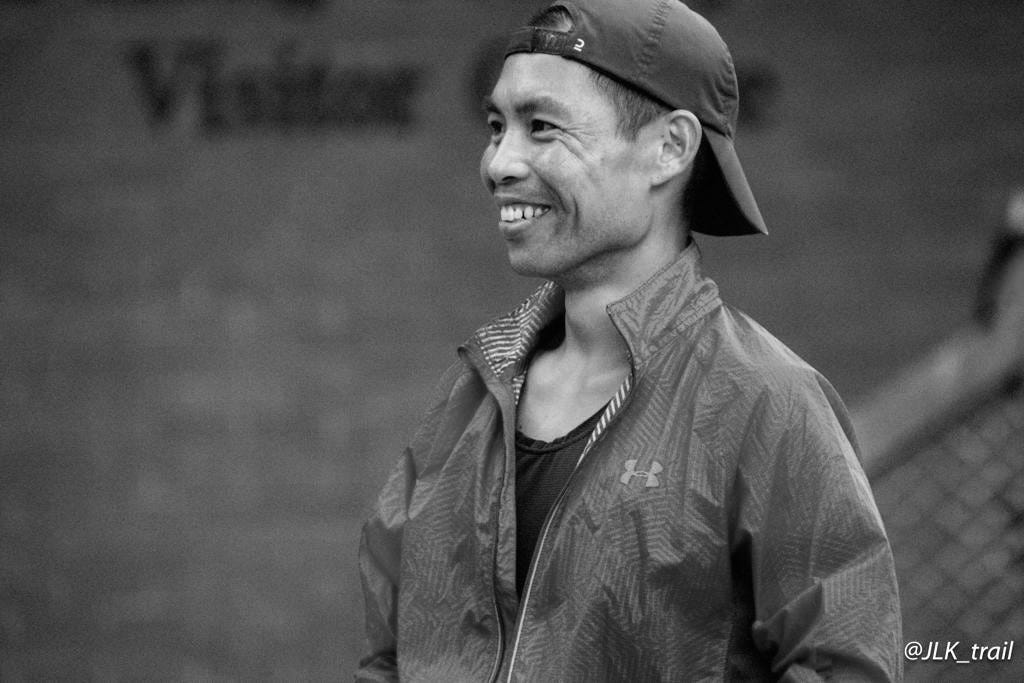

Lost on Purpose: The Life and Adventures of a Runner That Enjoyed Doing Nothing

My living obituary to acknowledge the preciousness of life and time. I'm fine. This is just an exercise.

James said he was going for a run and would be back soon. He didn’t say when or where, but when he packed a PB&J sandwich and slathered on sunblock, we knew it would be a while. As the sun set, we started to worry. By the next day, with still no sign of him, we called for help. Eventually, the court officially declared him dead under the presumption of death rule.

Predictable in some ways, James started every day with a run, no matter the conditions, the time zone, or the chaos of the night before. He’d return with the most unexpected stories. Whether it was the lively beaches of Da Nang at dawn, endlessly circling Bangkok's Lumphini park, or sliding open the door of a camper van in the pitch-black New Zealand winter, he always found something worth seeing—and something worth sharing.

He kept things simple. His breakfast routine rarely deviated: hard-boiled eggs and a banana. When avocados were in season and on sale, he called it luxury. "Unlimited avocados—that’s when you know you’re rich," he said. He had a way of appreciating the little things.

There were also things he hated. Bruised fruit and spoiled vegtables topped the list, along with waking up after sunrise. Anything car-related—parking, reversing, fixing—was his undoing. His disdain for those tasks was balanced by a love of sharing dessert. Maricar called it "the tax." He never ordered his own, choosing instead to sample bites from his children’s plates, savoring the idea that "everything tastes better shared."

His favorite thing to do was nothing—as long as he had someone to share it with. And he shared plenty of nothing with his family, often in the simplest ways: walking side by side or sharing a meal.

He was a storyteller. Though he struggled to recall numbers, lyrics, or movie titles, he could conjure up faces and details from thin air to make someone feel appreciated and recognized.

He wrote a memoir because, well, he thought it would be a cool idea and well, his memory. It took him a while to find the story within the story, but eventually, he got it together and published it in April. Naturally, he forced his children to read it, as if it was some kind of family obligation. The hardest part? Creating a cover. Have you ever seen him draw anything artistic? Let's just say the cover was a labor of love, not necessarily a work of art. But that was James—determined to follow through on his ideas, no matter how messy or imperfect the execution.

Running was where he was at peace, though not every race went as planned. He DNF’d at the Hong Kong 100 after destroying his hamstrings and then positively split the Lantau 70 by botching his pacing and nutrition. But there were triumphs too: red-lining it at Macau, China Coast, and the King of the Hills (Sai Kung & Hong Kong), leaving everything on the trails and sometimes needing to lie down afterward—occasionally posing as if he’d passed out. He finished the Quad Dipsea in under 5 hours, a fact he took quiet pride in.

He was rarely overdressed, usually sporting a vest he swore by for keeping his core warm while leaving his arms free. Above 70 degrees? Shorts and barefoot-style sandals were all he needed. He loved the dry heat, and never missed an opportunity to bask in it.

Adventure wasn’t just an idea for James—it was a way of life. Adventure meant embracing the unexpected. He often got purposefully lost just to stumble onto something new. "Adventure is out there," he’d say, chasing it in his own way—a little recklessly, a little boldly. He lived knowing death was inevitable, and if it wanted to find him, it would have to catch him first. And that’s how he lived—and died—or maybe just got lost—on an adventure, daring life to keep up.

DISCLAIMER: I’m fine and well. Below is a bit more context about the living obituary…

“Everybody knows they’re going to die, but nobody believes it. If we did, we would do things differently,’ Morrie said.

‘So we kid ourselves about death,’ I said.

‘Yes, but there’s a better approach. To know you’re going to die and be prepared for it at any time. That’s better. That way you can actually be more involved in your life while you’re living. . .

Every day, have a little bird on your shoulder that asks, ‘Is today the day? Am I ready? Am I doing all I need to do? Am I being the person I want to be?...

The truth is, once you learn how to die, you learn how to live… Most of us walk around as if we’re sleepwalking. We really don’t experience the world fully because we’re half asleep, doing things we automatically think we have to do… Learn how to die, and you learn how to live.”

Why Am I Doing This? As I reflect on the life I want to live, I realize the importance of being present for the people who make it meaningful. That's why I'm starting a new tradition: writing living obituaries for my loved ones on their birthdays. It's a way to slow down, appreciate, and cherish the time we have together.

Happy birthday!

Amazing! Love the bit about avocados. This essay reminds me of Forest Gump’s travels.